![]() Guilherme H. Silva1

Guilherme H. Silva1 ![]() ,

, ![]() Jaquelini O. Zeni2 and

Jaquelini O. Zeni2 and ![]() Francisco Langeani1

Francisco Langeani1

PDF: EN XML: EN | Supplementary: S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 | Cite this article

Abstract

Adaptations in the head structures of fishes can influence food item selection and consumption in aquatic ecosystems. In this study, we tested the relationship between the morphology of the bony structure of the head (suspensorium, mandibular, hyoid, and branchial arches) and the consumption of food items in Loricariinae species. We hypothesize that osteological specializations in the head structures (i.e., mouth) can lead to differential consumption of resources. Despite the relatively high trophic similarity, food item consumption was not uniform among Loricariinae species. The phylogenetic reconstruction recovered morphological patterns already expected for Loricariinae, such as the sister taxa Hemiodontichthys and Reganella. Phylogenetic characters associated with shape, width, and structures in the suspensorium, and branchial arches were correlated with differences in detritus, sediment, and invertebrates consumption. Specifically, branchial arches characters were associated with the consumption of aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates, while suspensorium characters were linked to the consumption of sediment, superior plants, detritus, and aquatic invertebrates. These findings suggest that trophic specialization in loricariines is strongly influenced by the morphological differentiation of these structural features.

Keywords: Aquatic invertebrates, Branchial arches, Osteology, Suspensorium, Trophic ecology.

Adaptações nas estruturas bucais dos peixes podem influenciar a seleção e o consumo de itens alimentares nos ecossistemas aquáticos. Neste estudo, testamos a relação entre a morfologia de estruturas ósseas do crânio (suspensório, arco mandibular, arco hioide e arcos branquiais) e o consumo de itens alimentares em Loricariinae. Nossa hipótese é que especializações osteológicas nas estruturas do crânio (i.e., boca) podem levar a um consumo diferenciado de recursos alimentares. Apesar da similaridade trófica relativamente alta, o padrão de consumo de itens alimentares não foi uniforme entre as espécies de Loricariinae. A reconstrução filogenética recuperou padrões morfológicos já esperados para Loricariinae, como os táxons irmãos Hemiodontichthys e Reganella. Caracteres filogenéticos associados à forma, largura e estruturas no suspensório e nos arcos branquiais foram correlacionados com diferenças no consumo de detritos, sedimentos e invertebrados. Em particular, os caracteres dos arcos branquiais foram associados ao consumo de invertebrados aquáticos e terrestres, enquanto os caracteres do suspensório foram associados ao consumo de sedimentos, plantas superiores, detritos e invertebrados aquáticos. Essas descobertas sugerem que a especialização trófica em loricaríneos é fortemente influenciada pela diferenciação morfológica dessas características estruturais.

Palavras-chave: Arcos branquiais, Ecologia trófica, Invertebrados aquáticos, Osteologia, Suspensório.

Introduction

Loricariidae is the largest family among the Siluriformes with almost 1,100 valid species distributed into six valid subfamilies Lithogeninae, Delturinae, Rhinelepinae, Loricariinae, Hypoptopomatinae, Hypostominae (Lujan et al., 2015; Roxo et al., 2019; Londoño-Burbano, Reis, 2021; Fricke et al., 2024). The family is found in a wide range of aquatic environments across South America and southern Central America (Armbruster, 2004; Lujan et al., 2015) showing a high morphological complexity, especially in cranial bones (Schaefer, Lauder, 1996; Rapp Py-Daniel, 1997). The Loricariinae is the most diverse subfamily with 274 species (Fricke et al., 2024) that often share the same habitats and possibly have similar ecological niches, such as the genera Hemiodontichthys, Loricaria, Loricariichthys, and Reganella (Rapp Py-Daniel, 1997; Covain, Fisch-Muller, 2007; Brejão et al., 2013; Reinas et al., 2022).

Most of the loricarids are algae and detritus (i.e., fine, and coarse particulate organic matter) eaters and act as a link of energy transference between lower to higher trophic levels in the Neotropical aquatic ecosystems (Delariva et al., 2013; Corrêa et al., 2021). However, some loricarids have specialized diets like wood (Hypostomus, Panaque and Pterygoplichthys genera), seeds (Crossoloricaria and Loricaria genera), and invertebrates (Spatuloricaria genus), making them great organisms for understanding not only trophic diversity but also niche partitioning (Armbruster, 2004; German, 2009; German et al., 2010; Lujan et al., 2012; Black, Armbruster, 2021). In this context, loricariids have a fundamental role in ecosystem services, such as organic matter decomposition, nutrient cycling, riparian vegetation control, and water purification (Winemiller et al., 2006; German, 2009; Pelicice et al., 2023).

All these are important functions often associated with their feeding habits, which are mediated by their sucking mouths and scraping teeth (de Pinna, 1998; Cardone et al., 2006; Krings et al., 2023). Burress et al. (2023) have demonstrated that food items can act as a selective pressure, strongly impacting jaw evolution and specialization in herbivorous cichlids. Differences in how these species obtain food have been revealed as one of the main keys to high adaptive radiation in Neotropical environments (Martin, Wainwright, 2011; López-Fernández et al., 2013; Arbour et al., 2020). However, the same pattern was not observed in extremely diverse environments such as coral reefs, where high morphological overlap between trophic groups reveals that fish with similar morphology may have different feeding strategies (Bellwood et al., 2006; Pombo-Ayora et al., 2020). For loricarids, Schaefer, Lauder (1986) described that some functional adaptations in their head structures, such as the presence of specialized teeth in the jaws and a higher number of gill rakers would be responsible for the selection of food particles. Melo et al. (2004) and Lujan, Armbruster (2012) investigating morphofunctional parameters of osteological structures of the head, such as the mandibular arch, demonstrated that the functional anatomy of the mouth apparatus of Loricariinae is extremely specialized in the selection and ingestion of food items, such as aquatic invertebrates, from sandy substrates. Furthermore, they emphasized that the diversity of morphological patterns found in loricarids comes from the conservation of phylogenetic structures and species’ adaptive radiation and trophic specialization (Lujan, Armbruster, 2012).

Morphological traits and ecological features are intrinsically linked, with reciprocal influences shaping adaptive responses. In loricarids, for instance, variation in collagen density present in the oral disk reflects this interaction, as species from turbulent environments usually have thicker attaching suction cups (Bressman et al., 2020; Krings et al., 2023). According to Bressman et al. (2020), this character can influence foraging and food intake processes because most species with highly fimbriate oral discs are specialized in feeding on soft substrates. Additionally, the bone structures of the suspensorium can also have a major influence on foraging efficiency and prey capture, since they determine the type of resource that can be used by suckermouth species (Gromova, Makhotin, 2022). The suspensorium-hyoid connections are reinforced, as seen in Ancistrus cf. triradiatus, where this adaptation likely prevents structural collapse during high suction, facilitating substrate adhesion and efficient resource exploitation (Schaefer, 1990; Armbruster, 2004; Geerinckx et al., 2007). However, Black, Armbruster (2021) found multiple species of armored catfishes with different jaw morphologies that were classified into the same trophic category. According to the authors, ecological traits act as important selective factors shaping jaw diversity, with habitat characteristics (e.g., surface types, flow regime, water depth and channel width) playing a more significant role than food consumption.

In cichlid fishes, it is assumed that the pharyngeal teeth operate separately from the oral ones, as they handle food processing, while the oral’ are predominantly used for capturing prey (Liem, Osse, 1975; Wainwright, 2007). Lujan, Armbruster (2012) suggest that despite being treated as separate entities, coordinated evolution is probable among decoupled structures like that. Despite that, most research on trophic morphology in loricariids places significant emphasis on the mandibular arch (i.e., oral jaw) as a potential structure involved in food ingestion, yet the role of the loricariid jaw mechanism and its ecological connection remains ambiguous (Black, Armbruster, 2022a). However, other bone sets such as the hyoid arch, suspensorium, and branchial arches could also be related to this process, since the biological mechanisms in loricariids buccal apparatus have not been entirely understood (Adriaens et al., 2001; Lujan, Armbruster, 2012). Gromova, Makhotin (2022) propose that in Teleostei species with specialized feeding mechanisms, the importance of the maxilla and premaxilla in food acquisition decreases, while other head components, such as the suspensorium and neurocranium structures, may have a major influence. In this context, we aim to test if there is an association between the morphology of the head skeletal structures (suspensorium, mandibular, hyoid, and branchial arches) and the diet of Loricariinae species. We hypothesize that osteological specializations in the head structures can lead to differential consumption of food resources.

Material and methods

Trophic analysis. For the trophic analysis, we selected adult specimens from sixteen species of loricariids: Furcodontichthys novaesi Rapp Py-Daniel, 1981, Hemiodontichthys acipenserinus (Kner, 1853), Limatulichthys griseus (Eigenmann, 1909), Limatulichthys punctatus (Regan, 1904), Loricaria cataphracta Linnaeus, 1758, Loricaria cf. luciae Thomas, Rodriguez, Carvallaro, Froehlich & Castro, 2013, Loricariichthys acutus (Valenciennes, 1840), Loricariichthys anus (Valenciennes 1835), Loricariichthys castaneus (Castelnau, 1855), Loricariichthys derbyi Fowler, 1915, Loricariichthys platymetopon Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1979, Proloricaria prolixa (Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1978), Pseudohemiodon platycephalus (Kner, 1853), Pseudoloricaria laeviuscula (Valenciennes, 1840), Reganella depressa (Kner, 1853), Spatuloricaria evansii (Boulenger, 1892). The species were selected based on the availability of material in zoological collections. The examined material was from DZSJRP, Coleção de Peixes do Departamento de Ciências Biológicas do Instituto de Biociências, Letras e Ciências Exatas, Universidade Estadual Paulista, São José do Rio Preto; INPA, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Manaus; LBP, Laboratório de Biologia de Peixes, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Botucatu; MBML, Coleção de Peixes do Instituto Nacional da Mata Atlântica, Santa Teresa, Espírito Santo, Brasil; MCP, Museu de Ciências e Tecnologia da Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre; MZUEL, Museu de Zoologia da Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina; MZUSP, Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo; NUP, Coleção Ictiológica do Núcleo de Pesquisas em Limnologia, Ictiologia e Aquicultura, Universidade Estadual de Maringá; and ZUFMS, Coleção Zoológica da Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande. We analyzed seven to 20 specimens of each species (Tab. S1; Fig. 1), and voucher numbers and corresponding watersheds are listed in S2.

FIGURE 1| Map with the location of each specimen analyzed in this paper (outgroups taxa are not shown). Solid circles represent specimens from osteological analysis and open circles represent specimens from trophic analysis. Scale bar = 600 km.

The trophic evaluation was performed by analyzing the gut contents of the stomach and intestinal tract since the loricariid stomach alone is not directly involved in digestion (German, Bittong, 2009). Sampling was conducted via a ventral incision (Bowen, 1996). The gut contents were analyzed using a binocular stereomicroscope and three slides for each specimen were prepared for observation under an optical microscope with magnification up to 40 times. The food items were identified to the lowest possible taxonomic level and quantified according to the visually estimated volume occupied by the item considering the volume total of the stomach (Hyslop, 1980; Zeni, Casatti, 2014). When the stomachs were empty, we quantified the food items found in the intestines. After that, we clustered food items into eight categories: detritus (decomposed fine and coarse organic matter, and periphyton), sediment (sand, clay, or inorganic fragmented material), superior plant (pieces of leaves, roots, stems, spicules, trichomes, seeds, etc.), tecamoebas, filamentous algae, diatoms, aquatic invertebrates (autochthonous origin) and terrestrial invertebrates (allochthonous origin).

Osteological and phylogenetic analysis. To identify morphological patterns among the species, we performed a phylogenetic analysis with 23 terminal taxa representing Astroblepidae and five subfamilies of Loricariidae sensu Lujan et al. (2015), Londoño-Burbano, Reis, (2021) and Fricke et al. (2024) (Lithogeninae, Delturinae, Hypostominae, Hypoptopomatinae and Loricariinae). The ingroup was composed of the same 16 species of Loricariinae used for trophic analysis and comprised only valid species, the outgroup was composed of seven species, including representatives from the mentioned taxa, except for Loricariinae. The specimens used for osteological analysis, when available, were the same as those used in the trophic analysis (Fig. 1).

We prepared one to five specimens of each species for osteological studies by clearing and staining according to Taylor, Van Dyke (1985) (Tab. S1). The osteological terminology followed Schaefer (1987) and Paixão, Toledo-Piza (2009). Measurements followed Langeani et al. (2001) and were performed mainly on the left side of each specimen. The specimens were dissected, analyzed, and compared. Observations on the material were made with a binocular stereomicroscope. For comparative osteological analysis, 90 morphological and anatomical characters of the suspensorium, branchial, mandibular, and hyoid arches were carefully selected from classic works, known for their effectiveness in clarifying phylogenetic relationships, and based on studies that suggest correlations with feeding behaviors (Schaefer, Lauder, 1986; Rapp Py-Daniel, 1997; Adriaens et al., 2001; Fichberg, 2008; Lujan, Armbruster, 2012; Paixão, 2012; Brejão et al., 2013; Gromova, Makhotin, 2022). The characters were revised, and a new one is proposed (char. 55) (Tabs. S1, S3).

Phylogenetic analysis was performed on TNT v. 1.5 (Goloboff, Catalano, 2016). Before initiating the search, maximum trees in memory were expanded to 10.000. The reconstruction was executed with Traditional Search. The parameters were: Wagner trees with 1 random seed and 10 replications, Tree Bisection Reconnection (TBR) with 10 trees to save per replication and replace existing trees activated. A strict consensus was built from the equally parsimonious trees. The Bremer Index was utilized as a branch support measure and performed in TNT v. 1.5, using suboptimal trees with up to 10 steps more than the fundamental trees (Bremer, 1994). The consistency (CI) and retention (RI) indexes are indicated as CI = — and RI = — in cases that correspond to autapomorphies and are therefore not calculated by TNT. The transformations of character state were analyzed with WinClada (Nixon, 1999). The trees were rooted in Astroblepus sp.

Statistical analysis. To evaluate trophic similarity, we calculated the Bray-Curtis coefficient of the standardized average of the volume of each food item (%) in each species. To test if there were differences in the food items consumption between the species, covariance analyses were performed (one-way ANOVA, 9,999 permutations), with Tukey’s test with a significance level of p<0.05. The Tukey test was applied only when ANOVA showed significant results. We built boxplots to graphically visualize the differences in the item’s consumption among species.

To test the relationship between osteological features and food item consumption, we performed a Canonical Correspondence Analyses (CCA) using the trophic matrix (i.e., average of the volume of each food item) of the species (without the diatoms category that didn’t show differences among the species) and the characters matrix. Initially, the characters were categorized into groups of the suspensorium (1 to 19), hyoid arch (20 to 38), mandibular arch (39 to 51), and branchial arches (52 to 90). For each of the CCA’s model selection, we used the ordistepfunction in the vegan package, followed by an ANOVA with 9,999 permutations to test the significance of the model and to identify the most important osteological characters for each food item consumption. All statistical analyses and graphical projections were performed in R v. 3.4.4 software.

Results

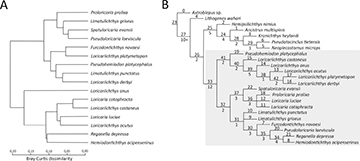

The phylogenetic analysis resulted in three equally parsimonious trees with a length of 364 steps, a consistency index of 0.340, and a retention index of 0.590. From these, a strict consensus cladogram was constructed (Fig. 2B). The list of synapomorphies for the consensus tree is available in Tab. S3.

FIGURE 2| The Bray-Curtis trophic dissimilarity among species analyzed in this paper (average = 0.08; SD = 0.03) (A). Strict consensus cladogram constructed from the 3 equally parsimonious trees found (364 steps; CI = 0.340; RI = 0.590) (B). Upper numbers indicate clade. Lower numbers indicate Bremer Support. The highlighted species represent those used in trophic analysis.

The phylogeny reveals that Loricariinae patterns are consistent with those identified by Rapp Py-Daniel (1997), where Hemiodontichthys acipenserinus was found as a sister species to Reganella depressa (clade 34, Fig. 2B), supported by one exclusive synapomorphy, presence of rakers in third basibranchial (char. 58, 0 → 1), and four non-exclusive synapomorphies, type of contact between metapterygoid and lateral ethmoid partially sutured (char. 5, 2 → 1); tiny size of premaxilla, smaller than 1/4 the size of the maxillary (char. 36, 2 → 0); connection of ceratohyal with epihyal with two sutures interspersed by cartilage (char. 47, 1 → 2); posterior process of first epibranchial conspicuous (char. 64, 0 → 1). Similarly, our findings align with Covain et al. (2016) who observed Hemiodontichthys, Limatulichthys and Pseudoloricaria in the same clade. The close phylogenetic relationships between Hemiodontichthys and Limatulichthys was also consistent with the findings of Covain et al. (2008), Rodriguez et al. (2011), and Londoño-Burbano, Reis (2021). Furthermore, our analysis also confirms the relationships between Loricaria and Spatuloricaria, as previously reported by Covain et al. (2008), Rodriguez et al. (2011), and Covain et al. (2016). However, our analysis did not recover the Loricariichthys group and the Loricaria–Pseudohemiodon group described by Covain, Fisch-Muller (2007), nor did it retrieve the Hemiodontichthyna and Planiloricaria groups sensu Rapp Py-Daniel (1997) and Armbruster (2004).

We observed an initial split leading to two clades. The first branch, supported by synapomorphies in the suspensorium and hyoid arches (e.g., bone extension of the hyomandibula and connection of ceratohyal with epihyal), includes all Loricariichthys species sister to Pseudohemiodon platycephalus. The other one, supported by synapomorphies in the suspensorium and branchial arches (e.g., connection of the preopercle with dermal plates and the number of rows of teeth on the lower pharyngeal tooth plate), with two smaller clades: one, predominantly supported by synapomorphies in the lower pharyngeal tooth plates, with Spatuloricaria evansii, sister to a polytomy formed by Proloricaria prolixa, Loricaria cf. luciae, and Loricaria cataphracta (clade 37, Fig. 2B) supported by four non-exclusive synapomorphies, anterior margin of ceratohyal serrated (char. 46, 0 → 1); posterior process of third epibranchial conspicuous (char. 66, 2 → 1) (S4); lateral sides of lower pharyngeal tooth plates covered with non-ossified rakers (char. 85, 0 → 1); presence of molariform teeth in upper and lower pharyngeal tooth plates (char. 86, 0 → 1), and two exclusive synapomorphies, presence of connection between lower pharyngeal tooth plates (char. 87, 0 → 1); thick width of the lower pharyngeal tooth plates (char. 88, 0 → 1) (S4); and the other, supported by a T-shaped preopercle canal with three exits, with a polytomy with Limatulichthys punctatus, Limatulichthys griseus, and a clade formed by Furcodontichthys novaesi, Pseudoloricaria laeviscula, and the sister taxa Reganella depressa and Hemiodontichthys acipenserinus.

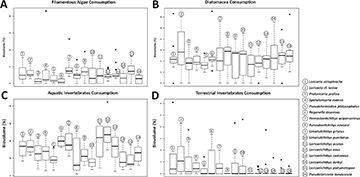

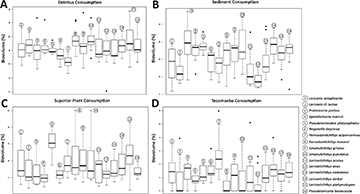

Detritus was the most consumed food item, occupying around 31.85% of the species’ stomach and intestines volume, followed by aquatic invertebrates with 28.60% and sediments with 21.00%. The items with lower representativity were terrestrial invertebrates (1.30%), tecamoebas (2.65%), filamentous algae (2.90%), diatoms (4.40%), and superior plants (8.55%) (Tab. 1). Trophic dissimilarity among species was low (mean = 0.08; sd= 0.03) (Fig. 2A). However, food consumption of most of the items, except for diatoms, was different among species (Tab. 2). Overall, some species were responsible for these differences and mostly in the ingestion of detritus, sediments, superior plants, tecamoebas and aquatic invertebrates (Fig. 3). Hemiodontichthys acipenserinus distinguished itself from more than half of the species analyzed by showing, on average, lower consumption of detritus and sediments and higher consumption of tecamoebas and aquatic invertebrates, while the species Furcodontichthys novaesi, Limatulichthys punctatus, Loricariichthys acutus and Loricariichthys anus showed lower consumption of sediment and higher consumption of aquatic invertebrates compared to most species (Fig. 3; Tab. S5). In addition, Pseudohemiodon platycephalus and Reganella depressa exhibited higher consumption of superior plants and aquatic invertebrates, respectively, compared to most other species (Fig. 4; Tab. S5).

TABLE 1 | Number of analyzed stomachs (N) and the average of volume for each food item for each species and for all Loricariidae species.

Species | N | Detritus | Sediment | Superior plants | Tecamoeba | Algae | Diatoms | Invertebrates | |

Aquatic | Terrestrial | ||||||||

Furcodontichthys novaesi | 10 | 26.161 | 18.779 | 5.860 | 3.007 | 0.603 | 4.929 | 39.785 | 0.878 |

Hemiodontichthys acipenserinus | 20 | 30.306 | 27.797 | 15.195 | 2.478 | 1.386 | 3.433 | 19.153 | 0.254 |

Limatulichthys griseus | 10 | 21.389 | 16.899 | 9.143 | 5.098 | 4.225 | 4.579 | 38.152 | 0.516 |

Limatulichthys punctatus | 13 | 37.706 | 21.765 | 10.784 | 0.743 | 2.505 | 4.967 | 21.530 | 0.000 |

Loricaria cataphracta | 10 | 31.017 | 17.064 | 8.655 | 2.851 | 2.908 | 4.782 | 31.565 | 1.158 |

Loricaria cf. luciae | 11 | 33.500 | 12.806 | 7.196 | 1.720 | 3.139 | 6.105 | 34.055 | 1.479 |

Loricariichthys acutus | 11 | 32.087 | 23.371 | 9.794 | 2.247 | 3.832 | 4.005 | 24.022 | 0.643 |

Loricariichthys anus | 10 | 37.435 | 27.954 | 9.641 | 1.845 | 2.585 | 4.048 | 15.818 | 0.675 |

Loricariichthys castaneus | 18 | 31.773 | 13.743 | 7.698 | 2.388 | 2.472 | 3.282 | 38.643 | 0.000 |

Loricariichthys derbyi | 13 | 30.263 | 7.764 | 6.041 | 0.836 | 2.407 | 3.857 | 48.744 | 0.090 |

Loricariichthys platymetopon | 11 | 30.268 | 19.221 | 7.705 | 2.486 | 3.283 | 4.106 | 32.580 | 0.352 |

Proloricaria prolixa | 10 | 30.047 | 29.613 | 6.441 | 2.812 | 0.779 | 3.634 | 25.823 | 0.853 |

Pseudohemiodon platycephalus | 10 | 33.416 | 27.841 | 9.047 | 3.384 | 1.669 | 5.062 | 19.457 | 0.124 |

Pseudoloricaria laeviuscula | 16 | 37.254 | 22.703 | 11.878 | 2.365 | 4.112 | 4.525 | 17.059 | 0.105 |

Reganella depressa | 10 | 33.746 | 24.657 | 6.677 | 2.975 | 1.209 | 5.345 | 25.326 | 0.066 |

Spatuloricaria evansii | 7 | 33.348 | 24.766 | 4.984 | 1.576 | 4.622 | 4.078 | 26.087 | 0.541 |

Average |

| 31.857 | 21.046 | 8.546 | 2.426 | 2.608 | 4.421 | 28.612 | 0.483 |

TABLE 2 | F-values and p-values for the covariance analysis (ANOVA) and Tukey test for each food item consumed by Loricariidae species.

Food item | F-value | p-value |

Detritus | 3.871 | < 0.05 |

Inorganic sediment | 8.236 | < 0.05 |

Superior plants | 4.566 | < 0.05 |

Tecamoeba | 4.204 | < 0.05 |

Filamentous Algae | 3.016 | < 0.05 |

Diatoms | 0.862 | 0.60 |

Aquatic invertebrates | 9.088 | < 0.05 |

Terrestrial invertebrates | 2.458 | < 0.05 |

FIGURE 3| Boxplot with filamentous Algae (A), diatoms (B), aquatic (C) and terrestrial invertebrates (D) consumption for each species. For pairwise p-values, see Tab. S5.

FIGURE 4| Boxplot with detritus (A), sediment (B), superior plant (C) and tecamoeba (D) consumption for each species and the p-value. For pairwise p-values, see Tab. S5.

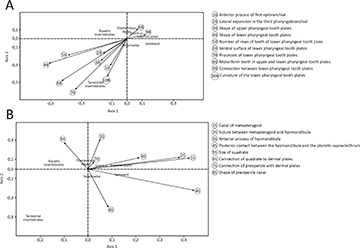

The correlation between osteological structures of suspensorium (F = 6.65; p-value = 0.014) and branchial arches (F = 6.03; p-value = 0.003) was statistically significant to the species diet, while the hyoid (F = 0.44; p-value = 0.94) and mandibular arches (F = 3.05; p-value = 0.08) had no significance. For the branchial arches and suspensorium, 10 and eight characters were statistically significant, respectively (Tab. 3). Most of the branchial arches characters, such as the shape and processes of the lower pharyngeal tooth plates, the number of tooth rows, and the presence of molariform teeth, were associated with the consumption of aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates (Tab. 3; Fig. 5A). In contrast, suspensorium characters, including the metapterygoid canal, the suture between the metapterygoid and hyomandibula, the posterior contact with the pterotic-supracleithrum, and the shape of the preopercle canal, were linked to the consumption of sediment, superior plants, detritus, and aquatic invertebrates (Tab. 3; Fig. 5B). The structural variation is related to distinct patterns of resource use in Loricariinae species.

TABLE 3 | Characters from suspensorium and branchial arches with a significant relationship with Loricariidae species diet (ID in Tab. S1).

| ID in Tab. S1 | ID in CCA plot | Character | p-value |

Suspensorium | 6 | 1S | Canal of metapterygoid | 0.020 |

9 | 2S | Suture between metapterygoid and hyomandibula | 0.010 | |

12 | 3S | Anterior process of hyomandibula | 0.010 | |

13 | 4S | Posterior contact between the hyomandibula and the pterotic-supracleithrum | 0.010 | |

14 | 5S | Size of quadrate | 0.010 | |

15 | 6S | Connection of quadrate to dermal plates | 0.010 | |

18 | 7S | Connection of preopercle with dermal plates | 0.020 | |

19 | 8S | Shape of preopercle canal | 0.003 | |

Branchial arches | 63 | 1B | Anterior process of first epibranchial | 0.004 |

75 | 2B | Lateral expansion in the third pharyngobranchial | 0.009 | |

79 | 3B | Shape of upper pharyngeal tooth plates | 0.010 | |

80 | 4B | Shape of lower pharyngeal tooth plates | 0.002 | |

82 | 5B | Number of rows of teeth of lower pharyngeal tooth plate | 0.020 | |

83 | 6B | Ventral surface of lower pharyngeal tooth plates | 0.020 | |

84 | 7B | Processes of lower pharyngeal tooth plates | 0.006 | |

86 | 8B | Molariform teeth in upper and lower pharyngeal tooth plates | 0.010 | |

87 | 9B | Connection between lower pharyngeal tooth plates | 0.010 | |

89 | 10B | Curvature of the lower pharyngeal tooth plates | 0.005 |

FIGURE 5| Distribution of the osteological characters from branchial arches (A) and suspensorium (B) in the multidimensional space with the food items.

Discussion

The diet of the loricarids was predominantly composed of detritus and sediments, constituting 52.90% of the gut contents. This aligns partially with the feeding patterns described for Neotropical loricarids, which are known to primarily feed on detritus and algae (Uieda, 1984; Hahn et al., 1997; Casatti et al., 2005; Côrrea et al., 2021).

The consumption of aquatic invertebrates (28.61% of total intake) was higher than that of filamentous algae, ranking as the third most ingested item. This pattern aligns with findings for Loricariichthys anus (Côrrea et al., 2021) and Proloricaria lentiginosa, which exhibit a tendency toward malacophagy (Salvador-Jr et al., 2009). Given that loricariids graze on periphyton, a microhabitat rich in small invertebrates, the ingestion of these organisms is expected. Although the species exhibited high trophic similarity, plasticity was observed, particularly in the consumption of detritus, sediments, and aquatic invertebrates. The morphology of the branchial and suspensorium structures was linked to the species diets, with a significant impact on most of the ingested items (Fig. 5). These results indicate that Loricariinae with fewer teeth are less likely to be scrapers and are more likely to be substrate pickers.

Catfishes are often credited as detritivores fish, and like other animals in this group, they primarily feed to attend to their protein necessities (Bowen et al., 1995; Raubenheimer et al., 2005). In fact, detritus represents the most consumed item in our study (31.85%), however the intake of other items with aggregated energetic value (e.g., tecamoebas, superior plants and invertebrates) was significantly high for Hemiodontichthys acipenserinus, Loricaria cf. luciae, Loricariichthys derbyi, Loricariichthys griseus, Loricariichthys platymetopon and Pseudoloricaria laeviscula, Loricariinae taxa with fewer mouth teeth. These species usually sharesimilar ecological niches (Rapp Py-Daniel, 1997; Covain, Fisch-Muller, 2007; Brejão et al., 2013), and our results suggest the existence of differential feeding selection levels in these fish possibly associated with morphological differences. For example, although superior plants (e.g., roots, leaves, stems, and seeds) made up less than 10% of the gut contents (Tab. 1), their consumption was significant higher in Hemiodontichthys acipenserinus, Loricaria cataphracta, Loricaria cf. luciae, Pseudohemiodon platycephalus, and Reganella depressa (Fig. 4) and this was correlated with well-developed lower pharyngeal tooth plates (Tab. 3; Fig. 5A). Armbruster (2004) observed the presence of pulverized seeds in the guts of Crossoloricaria and Loricaria and hypothesized that their molariform teeth and strong pharyngeal jaws are adaptations for seed-eating. He also noted that the posterolateral process on their ceratobranchial 5 bone was associated with an increased musculature likely needed for crushing seeds. Our analysis seems to corroborate this since the ceratobranchial 5 is enlarged, wide, sutured or tightly bound to itself, and has molariform teeth in all analyzed species of Loricaria and in Spatuloricaria evansii. We also observed a significant correlation between the vegetal material intake and the characteristics of the metapterygoid bone in the suspensorium (Tab. 3; Fig. 5A). Moroti et al. (2021), while studying communities, expressed that analyzing species phylogenetic relationships helps understand community dynamics, including resource partitioning. Despite needing more studies, our findings suggest a connection between the phylogenetic signal of the bony structure of the head and the granivorous diet in Loricariinae.

Supporting Black, Armbruster (2021, 2022a), we also found no significant correlation between the mandibular arch (i.e., oral jaws) and trophic data. However, the morphology of the branchial and suspensorium structures was linked to the species diets, with significant importance on the most consumed food items (Figs. 5A–B). Studies have shown that a larger area for muscle attachment to bone structures in the head allows for increased mobility of these bones within the oral and branchial cavity (Schaefer, Lauder, 1986; Schaefer, 1997; Geerinckx et al., 2007; Makhotin, Gromova, 2022). Distinctive features within the branchial arches have been observed in most species of Loricariinae investigated here, but unfortunately, the high morphological variation of branchial elements in loricarids makes it difficult to determine the polarity of character states and identify apomorphic traits, as indicated by Rapp Py-Daniel (1997) (Tabs. S1, S3, S4). Nonetheless, some of the osteological characteristics of branchial arches structures may lead to a more efficient selection process, resulting in the consumption of more energetic items. For example, the presence of an anterior process in the first epibranchial (Tab. 3; Fig. 5A), which varies in shape and orientation across different species, was linked to an increased ingestion of terrestrial invertebrates (Fig. 5A). The presence of a lateral expansion on the third pharyngobranchial in Hemiodontichthys acipenserinus

(Fig. 6), Loricariichthys derbyi and Reganella depressa was also associated with the ingestion of more energetic food items, such as aquatic invertebrates (Tab. 1; Fig. 5A). Despite finding some phylogenetic and trophic correspondences, both species share similar spatial distribution and similar ecological niche (Brejão et al., 2013; Reinas et al., 2022), which can also explain the similar trophic pattern.

FIGURE 6| Osteological sets of characters from Hemiodontichthys acipenserinus (DZSJRP 21189, 106.62 mm SL). Solid portions in gray represent cartilaginous tissue. Suspensorium (A), mesial view, left side. Arrow points to region of the suture between the hyomandibula and the neurocranium and indicates the posteroanterior direction. Scale bar = 1 mm. Branchial arches elements (B), dorsal view. Scale bar = 4 mm.

The absence of molariform teeth in the upper and lower pharyngeal plates of most of the examined species, including Furcodontichthys novaesi, Hemiodontichthys acipenserinus, Pseudohemiodon platycephalus, Pseudoloricaria laeviuscula and all analyzed species of Limatulichthys and Loricariichthys, was associated with increased consumption of terrestrial invertebrates (Tab. 3; Fig. 5A), which were predominantly found uncrushed. Moreover, the presence of processes in the lower pharyngeal tooth plates, along with the absence of curvature in these plates (Tab. 3; Fig. 5A), were associated with the higher ingestion of aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates, while morphological variations in their lower pharyngeal plates, such as the presence of a dorsal process in the anterior, posterior or both margins of the plates, the absence of connection between the lower pharyngeal plates, and a flat shape were associated with high ingestion of tecamoebas, terrestrial and aquatic invertebrates (Tab. 3; Fig. 5A).

Black, Armbruster (2021) argue that the diversity in jaw shape among loricariids is likely more influenced by substrate types and flow regimes than by any specific food item. They, along with Zeni et al. (2020a), suggest that trophic traits are influenced by the interaction between morphology and environmental conditions (Zeni et al., 2020b). In contrast, our results indicate that some morphological variations in branchial and suspensorium characters may reflect a more sophisticated selection process for food items with higher energetic value.

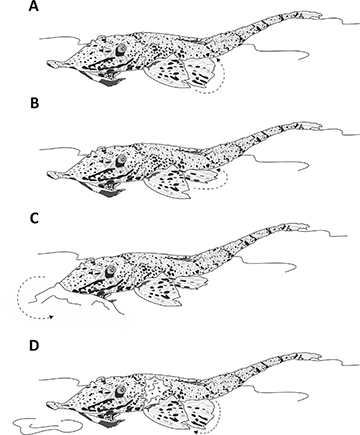

Hemiodontichthys acipenserinus provides a good example of how the interaction among morphology (Fig. 6), environmental factors, and behavior can influence trophic patterns in loricarids. This species ingested significantly lower amounts of sediment and higher amounts of tecamoebas and aquatic invertebrates, despite having a similar ecological habitat to species such as Limatulichthys punctatus and Reganella depressa. This stands out because tecamoebas and aquatic invertebrates in loricarids diet are positively related to sediment intake (Cardone et al., 2006; Villares-Junior et al., 2016). Hemiodontichthys acipenserinus exhibits solitary and nocturnal foraging behavior, using its pectoral and pelvic fins to move forward, bury the snout and oral disk in the substrate, then elevates its body and draws particles into the oral cavity for food selection, and finally expel sediment clouds through the opercular openings (Brejão et al., 2013) (Fig. 7). This behavior differs from the scraping behavior observed in other Loricariidae (Keenleyside, 2012) and explains most of the observed trophic pattern. This aspect can significantly influence variations in food consumption between the dry and rainy seasons for these animals (Côrrea et al., 2021). Moreover, for freshwater fish, it has been suggested that food availability in the environment is also an important variable for items consumption (Zeni, Casatti, 2014). In fact, many species feed on different food items in response to changes in resource availability (Allan, 2004; Mortillaro et al., 2015). Since the whiptail catfishes analyzed in this study are distributed across diverse habitats (Fig. 1) and captured in different seasons (e.g., dry and rainy seasons), they are influenced by environmental variations, this also affects the trophic patterns found.

FIGURE 7| Feeding behavior of Hemiodontichthys acipenserinus. Move forward using pectoral and pelvic fins (A), pelvic fins provide most of the support (B) while the snout and oral disc is buried into the substrate (C), elevates its body to draw particles into the oral cavity for selection, and expels sediment through the opercular openings (D).

However, the morphology of the cranial apparatus in Loricariinae, particularly in the tribe Loricariini, also plays a functional role in selecting specific food items. Therefore, changes in diet solely due to resource abundance are not likely to be the only reason for the differences observed in this study. As a result, diet also relies on the intrinsic structural characteristics of the species (de Pinna, 1998; Delariva, Agostinho, 2001; Villares-Junior et al., 2016). In fact, Delariva, Agostinho (2001) reported that Rhinelepis aspera Spix & Agassiz 1829 (Loricariidae: Hypostominae), which ingests small amounts of sediment, has adaptations in the branchial arches to facilitate the selection of food items. This is consistent with our findings for Hemiodontichthys acipenserinus (i.e., lower sediment intake and more energetic items) and other species in this paper (Figs. 5A–B). Notwithstanding, further research is necessary to enhance our understanding of how the head structures of loricariids correlate with the selection processes of more energetic items from substrate.

Finally, the phylogenetic reconstruction in this study was conducted to establish morphological patterns and similarities among species rather than propose or discuss established phylogenetic hypotheses. Nonetheless, we believe its descriptive contribution is relevant for understanding evolutionary relationships, ecological processes related to food acquisition and behavioral patterns. Additionally, there is potential future opportunity to investigate the branchial arches from a global perspective, considering that many structures are fused, and their functions are interdependent. Black, Armbruster (2022b) found no correlation between diet and phylogeny in loricariids, which can be attributed to multiple convergent events. However, they observed that evolutionary rates correlate with trophic patterns, highlighting the complexity of interpreting ecological traits in phylogenetic studies. This suggests that as loricariids occupy diverse ecological niches, oral jaw shape evolves more rapidly, a pattern that may also apply to the suspensorium and branchial arches. Most studies on the functional anatomy, trophic morphology, morphometry, and biomechanics of loricarids (Schaefer, Lauder, 1986; Schaefer, Lauder, 1996; Delariva, Agostinho, 2001; Lujan, Armbruster, 2012; Black, Armbruster, 2021, 2022a, b; Gromova; Makhotin, Gromova, 2022) have focused on the influence of the mandibular arch on swallowing and food selection. The present study demonstrated that suspensorium and mainly branchial arches structures were linked to the consumption of specific food items, particularly detritus, vegetal material, tecamoebas and invertebrates. These findings indicate that these anatomical features play some role in the process of selecting and acquiring particulate material from the ingested substrate.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Aléssio Datovo (MZUSP), Carla S. Pavanelli (NUP, UEM), Fernando Jerep (UEL), Carlos A. S. Lucena (MCP), Gustavo Graciolli (UFMS), Helio Q. Fernandes (INMA/MCTI), Lúcia Helena Rapp Py-Daniel (INPA), Flávio A. Bockmann (LIRPP, and Osvaldo T. Oyakawa (MZUSP), for the specimens provided and for the support in the scientific collections. In special Flavio C. T. Lima (UNICAMP) and Anderson Ferreira (UFGD) for the donation, respectively, specimens and guts of Hemiodontichthys acipenserinus. We also thank the Laboratory of Ichthyology UNESP/IBILCE for the support during the research development. Financial support came from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq 305.940/2011–0, 306.566/2014–1, 305.756/2018–4, and 313769/2023–0 to FL), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES to GHS), São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP 2018/06033–1 to JOZ), and UEMG (Edital 10/2022 PQ/UEMG to JOZ).

References

Adriaens D, Aerts P, Verraes W. Ontogenetic shift in mouth opening mechanisms in a catfish (Clariidae: Siluriformes): a response to increasing functional demands. J Morphol. 2001; 247(3):197–216. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4687(200103)247:3<197::AID-JMOR1012>3.0.CO;2-S

Allan JD. Landscapes and riverscapes: the influence of land use on stream ecosystems. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2004; 35:257–84. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.35.120202.110122

Arbour JH, Montaña CG, Winemiller KO, Pease AA, Soria-Barreto M, Cochran-Biederman JL et al. Macroevolutionary analyses indicate that repeated adaptive shifts towards predatory diets affect functional diversity in Neotropical cichlids. Biol J Linn Soc. 2020; 129(4):844–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/blaa001

Armbruster JW. Phylogenetic relationships of the suckermouth armoured catfishes (Loricariidae) with emphasis on the Hypostominae and the Ancistrinae. Zool J Linn Soc. 2004; 141(1):1–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2004.00109.x

Bellwood DR, Wainwright PC, Fulton CJ, Hoey AS. Functional versatility supports coral reef biodiversity. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2006; 273(1582):101–07. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3276

Black CR, Armbruster JW. New method of isotopic analysis: baseline-standardized isotope vector analysis shows trophic partitioning in loricariids. Ecosphere. 2021; 12(5):e03503. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3503

Black CR, Armbruster JW. Chew on this: oral jaw shape is not correlated with diet type in loricariid catfishes. PLoS ONE. 2022a; 17(11):e0277102. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0277102

Black CR, Armbruster JW. Evolutionary integration and modularity in the diversity of the suckermouth armoured catfishes. R Soc Open Sci. 2022b; 9(11):220713. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.220713

Bowen SH. Quantitative description of the diet. Fisheries techniques, 2nd edition. Am Fish Soc. 1996:513–32.

Bowen SH, Lutz EV, Ahlgren MO. Dietary protein and energy as determinants of food quality: trophic strategies compared. Ecology. 1995; 76(3):899–907. https://doi.org/10.2307/1939355

Brejão GL, Gerhard P, Zuanon J. Functional trophic composition of the ichthyofauna of forest streams in eastern Brazilian Amazon. Neotrop Ichthyol. 2013; 11(2):361–73. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1679-62252013005000006

Bressman NR, Armbruster JW, Lujan NK, Udoh I, Ashley-Ross MA. Evolutionary optimization of an anatomical suction cup: lip collagen content and its correlation with flow and substrate in Neotropical suckermouth catfishes (Loricarioidei). J Morphol. 2020; 281(6):676–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.21136

Burress ED, Piálek L, Casciotta J, Almirón A, Říčan O. Rapid parallel morphological and mechanical diversification of south american pike cichlids (Crenicichla). Syst Biol. 2023; 72(1):120–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syac018

Cardone IB, Lima-Junior SE, Goitein R. Diet and capture of Hypostomus strigaticeps (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) in a small Brazilian stream: relationship with limnological aspects. Braz J Biol. 2006; 66:25–33. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842006000100005

Casatti L, Rocha FC, Pereira DC. Habitat use by two species of Hypostomus (Pisces, Loricariidae) in Southeastern Brazilian streams. Biota Neotrop. 2005; 5(2):157–65. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1676-06032005000300012

Corrêa F, Tuchtenhagen TS, Pouey J, Piedras SRN, Oliveira EF. Trophic ecology of Loricariichthys anus (Valenciennes, 1835), (Loricariidae: Loricariinae) in a subtropical reservoir, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2021; 93:e20200438. https://doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765202120200438

Covain R, Dray S, Fisch-Muller S, Montoya-Burgos JI. Assessing phylogenetic dependence of morphological traits using co-inertia prior to investigate character evolution in Loricariinae catfishes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008; 46(3):986–1002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2007.12.015

Covain R, Fisch-Muller S, Oliveira C, Mol JH, Montoya-Burgos JI, Dray S. Molecular phylogeny of the highly diversified catfish subfamily Loricariinae (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) reveals incongruences with morphological classification. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2016; 94:492–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2015.10.018

Covain R, Fisch-Muller S. The genera of the Neotropical armored catfish subfamily Loricariinae (Siluriformes: Loricariidae): a practical key and synopsis. Zootaxa. 2007; 1462:1–40. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.1462.1.1

Delariva RL, Agostinho AA. Relationship between morphology and diets of six Neotropical loricariids. J Fish Biol. 2001; 58(3):832–47. https://doi.org/10.1006/jfbi.2000.1499.

Delariva RL, Hahn NS, Kashiwaqui EA. Diet and trophic structure of the fish fauna in a subtropical ecosystem: impoundment effects. Neotrop Ichthyol. 2013; 11(4):891–904. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1679-62252013000400017

Fichberg I. Relações filogenéticas das espécies do gênero Rineloricaria Bleeker, 1862 (Siluriformes: Loricariidae: Loricariinae). [PhD Thesis]. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 2008. Available from: https://doi.org/10.11606/T.41.2008.tde-17022009-115207

Fricke R, Eschmeyer WN, Van der Laan R. Eschmeyer’s catalog of fishes: genera, species, references. San Francisco: California Academy of Science; 2024. Available from: http://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/ichthyology/catalog/fishcatmain.asp

Geerinckx T, Brunain M, Herrel A, Aerts P, Adriaens D. A head with a suckermouth: a functional-morphological study of the head of the suckermouth armoured catfish Ancistrus cf. triradiatus (Loricariidae: Siluriformes). Belg J Zool. 2007;137(1):47.

German DP. Inside the guts of wood-eating catfishes: can they digest wood? J Comp Physiol B. 2009; 179(8):1011–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00360-009-0381-1

German DP, Bittong RA. Digestive enzyme activities and gastrointestinal fermentation in wood-eating catfishes. J Comp Physiol B. 2009; 179(8):1025–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00360-009-0383-z

German DP, Neuberger DT, Callahan MN, Lizardo NR, Evans DH. Feast to famine: the effects of food quality and quantity on the gut structure and function of a detritivorous catfish (Teleostei: Loricariidae). Comp Biochem Phys A. 2010; 155(3):281–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.10.018

Goloboff PA, Catalano SA. TNT version 1.5, including a full implementation of phylogenetic morphometrics. Cladistics. 2016; 32(3):221–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/cla.12160

Gromova ES, Makhotin VV. Function and morphology of the mandibular upper jaw in Teleostei: dependence on the feeding peculiarities. Russ J Mar Biol. 2022; 48(2):67–80. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063074022020043

Hahn NS Andrian IDF, Fugi R, Almeida VD. Ecologia trófica. A planície de inundação do alto rio Paraná: aspectos físicos, biológicos e socioeconômicos. Maringá: EDUEM; 1997.

Hyslop EJ. Stomach contents analysis—a review of methods and their application. J Fish Biol. 1980; 17(4):411–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.1980.tb02775.x

Keenleyside MH. Diversity and adaptation in fish behaviour. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012.

Krings W, Konn-Vetterlein D, Hausdorf B, Gorb SN. Holding in the stream: convergent evolution of suckermouth structures in Loricariidae (Siluriformes). Front Zool. 2023; 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12983-023-00516-w

Langeani F, Oyakawa OT, Montoya-Burgos JI. New species of Harttia (Loricariidae: Loricariinae) from the rio São Francisco basin. Copeia. 2001; 2001(1):136–42. https://doi.org/10.1643/0045-8511(2001)001[0136:NSOHLL]2.0.CO;2

Liem KF, Osse JWM. Biological versatility, evolution, and food resource exploitation in African cichlid fishes. Am Zool. 1975; 15(2):427–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/15.2.427

Londoño-Burbano A, Reis RE. A combined molecular and morphological phylogeny of the Loricariinae (Siluriformes: Loricariidae), with emphasis on the Harttiini and Farlowellini. PLoS ONE. 2021; 16:e0247747. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247747

López-Fernández H, Arbour JH, Winemiller KO, Honeycutt RL. Testing for ancient adaptive radiations in Neotropical cichlid fishes. Evolution. 2013; 67(5):1321–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12038

Lujan NK, Armbruster JW, Lovejoy NR, López-Fernández H. Multilocus molecular phylogeny of the suckermouth armored catfishes (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) with a focus on subfamily Hypostominae. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2015; 82:269–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2014.08.020

Lujan NK, Armbruster JW. Morphological and functional diversity of the mandible in suckermouth armored catfishes (Siluriformes: Loricariidae). J Morphol. 2012; 273(1):24–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.11003

Lujan NK, Winemiller KO, Armbruster JW. Trophic diversity in the evolution and community assembly of loricariid catfishes. BMC Evol Biol. 2012; 12:124. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-12-124

Makhotin VV, Gromova ES. Typology of the suspensorium structure of Teleost fishes in regard to their feeding. Inland Water Biol. 2022; 15(4):381–402. https://doi.org/10.1134/S199508292204037X

Martin CH, Wainwright PC. Trophic novelty is linked to exceptional rates of morphological diversification in two adaptive radiations of Cyprinodon pupfish. Evolution. 2011; 65(8):2197–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01294.x

Melo CE, Machado FD, Pinto-Silva V. Feeding habits of fish from a stream in the savanna of Central Brazil, Araguaia Basin. Neotrop Ichthyol. 2004; 2(1):37–44. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1679-62252004000100006

Moroti MT, Soares PT, Pedrozo M, Provete DB, Santana DJ. The effects of morphology, phylogeny and prey availability on trophic resource partitioning in an anuran community. Basic Appl Ecol. 2021; 50:181–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2020.11.005

Mortillaro JM, Pouilly M, Wach M, Freitas CEC, Abril G, Meziane T. Trophic opportunism of central Amazon floodplain fish. Freshw Biol. 2015; 60(8):1659–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12598

Nixon KC. WinClada ver. 1.0000. Published by the author, Ithaca, New York, USA, 1999–2002; 1999.

Paixão AD. Revisão taxonômica e filogenia do gênero Loricariichthys Bleeker, 1862 (Ostariophysi: Siluriformes: Loricariidae). [PhD Thesis]. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 2012. Available from: https://doi.org/10.11606/T.41.2012.tde-01052013-105133

Paixão AD, Toledo-Piza M. Systematics of Lamontichthys Miranda-Ribeiro (Siluriformes: Loricariidae), with the description of two new species. Neotrop Ichthyol. 2009; 7(4):519–68.https://doi.org/10.1590/S1679-62252009000400002

Pelicice FM, Agostinho AA, Azevedo-Santos VM, Bessa E, Casatti L, Garrone-Neto D et al. Ecosystem services generated by Neotropical freshwater fishes. Hydrobiologia. 2023; 850(12–13):2903–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-022-04986-7

de Pinna MD. Phylogenetic relationships of Neotropical Siluriformes (Teleostei: Ostariophysi): historical overview and synthesis of hypotheses. In: Malabarba LR, Reis RE, Vari RP, Lucena ZMS, Lucena CAS, editors. Phylogeny and classification of Neotropical fishes. Porto Alegre: Edipucrs; 1998. p.279–330.

Pombo-Ayora L, Coker DJ, Carvalho S, Short G, Berumen ML. Morphological and ecological trait diversity reveal sensitivity of herbivorous fish assemblages to coral reef benthic conditions. Mar Environ Res. 2020; 162:105102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2020.105102

Rapp Py-Daniel L. Phylogeny of the Neotropical armored catfishes of the subfamily Loricariinae (Siluriformes: Loricariidae). [PhD Thesis]. Tucson: The University of Arizona; 1997. Available from: https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/282395

Raubenheimer D, Lee KP, Simpson SJ. Does Bertrand’s rule apply to macronutrients? Proc R Soc B. 2005; 272(1579):2429–34. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3271

Reinas GCZ, Silva JC, Bialetzki A. Coexistence patterns between native and exotic juvenile Loricariidae in a Neotropical floodplain: an approach to resource partitioning. Hydrobiologia. 2022; 849(7):1713–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-022-04816-w

Rodriguez MS, Ortega H, Covain R. Intergeneric phylogenetic relationships in catfishes of the Loricariinae (Siluriformes: Loricariidae), with the description of Fonchiiloricaria nanodon: a new genus and species from Peru. J Fish Biol. 2011; 79(4):875–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2011.03047.x

Roxo FF, Ochoa LE, Sabaj MH, Lujan NK, Covain R, Silva GSC et al. Phylogenomic reappraisal of the Neotropical catfish family Loricariidae (Teleostei: Siluriformes) using ultraconserved elements. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2019; 135:148–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2019.02.017

Salvador-Jr LF, Salvador GN, Santos GB. Morphology of the digestive tract and feeding habits of Loricaria lentiginosa Isbrücker, 1979 in a Brazilian reservoir. Acta Zool. 2009; 90(2):101–09. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6395.2008.00336.x

Schaefer SA. Osteology of Hypostomus Plecostomus (Linnaeus): with a phylogenetic analysis of the loricariid subfamilies (Pisces: Siluroidei). Contrib Sci. 1987; 394:1–31. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.241283

Schaefer SA. Anatomy and relationships of the scoloplacid catfishes. Vol. 142. 1990.

Schaefer SA. The Neotropical cascudinhos: systematics and biogeography of the Otocinclus catfishes (Siluriformes: Loricariidae). Proc Acad Nat Sci Phila. 1997; 148:1–120.

Schaefer SA, Lauder GV. Historical transformation of functional design: evolutionary morphology of feeding mechanisms in loricarioid catfishes. Syst Zool. 1986; 35(4):489–508. https://doi.org/10.2307/2413111

Schaefer SA, Lauder GV. Testing historical hypotheses of morphological change: biomechanical decoupling in loricarioid catfishes. Evolution. 1996; 50(4):1661–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb03938.x

Taylor WR, Van Dyke GC. Revised procedures for staining and clearing small fishes and other vertebrates for bone and cartilage study. Cybium. 1985; 9(2):107–20. https://doi.org/10.26028/cybium/1985-92-001

Uieda VS. Ocorrência e distribuição dos peixes em um riacho de água doce. Rev Bras Biol. 1984; 44(2):203–13.

Villares-Junior GA, Cardone IB, Goitein R. Ecologia alimentar comparativa de quatro espécies simpátricas de Hypostomus em um rio do sudoeste brasileiro. Braz J Biol. 2016; 76(3):692–99. https://doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.00915

Wainwright PC. Functional versus morphological diversity in macroevolution. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2007; 38:381–401. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095706

Winemiller KO, Montoya JV, Roelke DL, Layman CA, Cotner JB. Seasonally varying impact of detritivorous fishes on the benthic ecology of a tropical floodplain river. J North Am Benthol Soc. 2006; 25(1):250–62. https://doi.org/10.1899/0887-3593(2006)25[250:SVIODF]2.0.CO;2

Zeni JO, Casatti L. The influence of habitat homogenization on the trophic structure of fish fauna in tropical streams. Hydrobiologia. 2014; 726(1):259–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-013-1772-6

Zeni JO, Hoeinghaus DJ, Roa-Fuentes CA, Casatti L. Stochastic species loss and dispersal limitation drive patterns of spatial and temporal beta diversity of fish assemblages in tropical agroecosystem streams. Hydrobiologia. 2020a; 847(18):3829–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-020-04356-1

Zeni JO, Sensato-Azevedo LM, Santos EF, Brejão GL, Casatti L. Habitat use, trophic, and occurrence patterns of Inpaichthys kerri and Hyphessobrycon vilmae (Pisces: Characidae) in amazonian streams. Neotrop Ichthyol. 2020b; 18(3):e200006. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0224-2020-0006

Authors

![]() Guilherme H. Silva1

Guilherme H. Silva1 ![]() ,

, ![]() Jaquelini O. Zeni2 and

Jaquelini O. Zeni2 and ![]() Francisco Langeani1

Francisco Langeani1

[1] Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” (UNESP), Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, R. Cristóvão Colombo, 2265, Jardim Nazareth, 15054-000 São José do Rio Preto, SP, Brazil. (GHS) guilherme.h.silva@unesp.br (corresponding author), (FS) francisco.langeani@unesp.br.

[2] Universidade do Estado de Minas Gerais (UEMG), Departamento de Biociências, Av. Juca Stockler, 1130, Belo Horizonte, 37900 106 Passos, MG, Brazil. (JOZ) jaquelini.zeni@uemg.br.

Authors’ Contribution

Guilherme H. Silva: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing.

Jaquelini O. Zeni: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing.

Francisco Langeani: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing-review and editing.

Ethical Statement

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

How to cite this article

Silva GH, Zeni JO, Langeani F. Head morphology and diet of whiptail catfishes (Loricariidae: Loricariinae). Neotrop Ichthyol. 2025; 23(1):e240113. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0224-2024-0113

Copyright

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Distributed under

Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0

© 2025 The Authors.

Diversity and Distributions Published by SBI

![]() Accepted February 13, 2025 by Rosemara Fugi

Accepted February 13, 2025 by Rosemara Fugi

![]() Submitted November 1, 2024

Submitted November 1, 2024

![]() Epub April 18, 2025

Epub April 18, 2025